Coughs and Sneezes

Coughs and Sneezes

One of the hot topics this year has been the Equine Influenza outbreak in the UK. This has been sufficiently significant that the racing programme was halted for a while and vaccination intervals were reduced to 6 monthly to allow access to competition venues.

Although respiratory problems have been highlighted this year, it is true that Equine Influenza outbreaks have occurred regularly in the past, admittedly not to this extent, but infections such as “Strangles” have a huge amount of impact on a regular basis. Therefore this shows that vigilance and bio-security are always important.

Here is a quick breakdown of common conditions to look for in horses that suffer from coughs and sneezes

Viral infections

These can cause both upper respiratory tract disease (i.e. nose and throat) and lower respiratory tract disease (lungs), which is generally more common. Signs that may be exhibited are:

Fever

Nasal discharge

Cough

Enlarged submandibular (under the jaw) lymph nodes

The common viruses encountered include:

Equine influenza

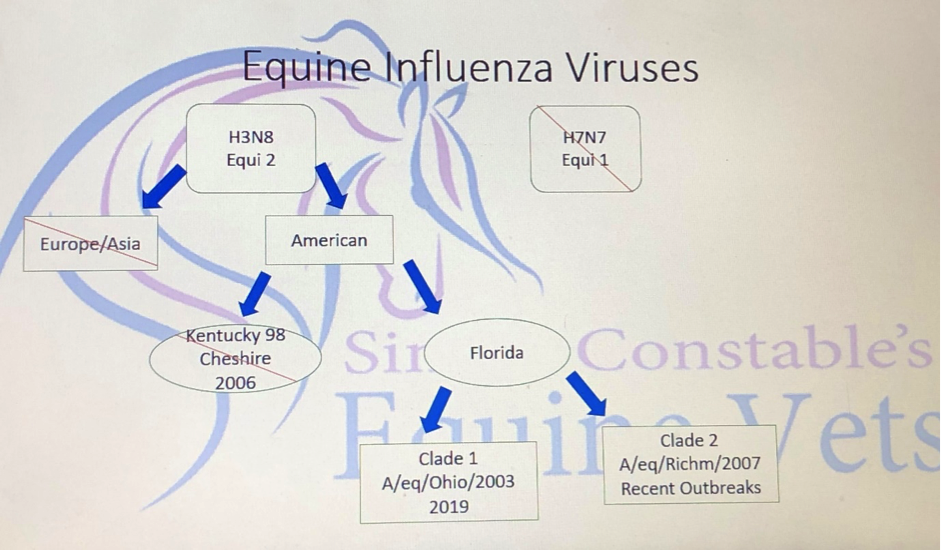

The latest outbreak of the virus has been the Florida strain, Clade 1 which has been a relative newcomer to Europe as a cause of Equine influenza outbreaks. Previous to 2019, the Clade 2 Florida strain has been the predominant one in Europe. This has a great deal of significance with regards to the most suitable vaccine because there is only one current vaccine available in the UK that has protection against both Florida Clade 1 and 2. Also this vaccine uses the latest in technology to present the vaccine virus in the most suitable manner to stimulate the most effective immunity.

In the natural infection, the virus spreads rapidly through a population and is caught by inhalation of droplets from infected horses. Direct contact nose to nose or transmission on buckets, clothing etc is the most likely way of passing on the infection. However, the droplets containing the influenza virus can move into the atmosphere and travel over more than a kilometre if the conditions are suitable.

More severe signs are seen in unvaccinated and younger horses, although sometimes vaccinated horses can show signs of influenza. This is more likely if one of the sub-optimal vaccines are used or if vaccine intervals have lapsed.

On inhaling the virus into the nasal passages they replicate in the cells of the nasal lining multiplying many times before re-emerging into the airways and potentially re-infecting other horses. Virus getting into the blood stream is a very small part of the Equine Influenza clinical signs.

These signs of Equine Influenza include depression, fever or high temperature, cough and a nasal discharge.

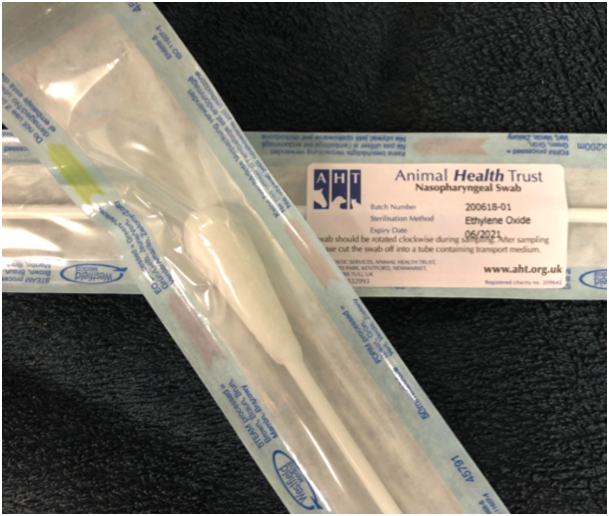

Diagnosis is either by naso-pharyngeal swab or looking at antibodies in the blood stream. The Animal Health Trust provides a fantastic monitoring service where samples are analysed and results texted and tweeted indicating the area where the outbreak has occurred.

Equine herpes viruses (EHV)

In addition to the respiratory signs of depression, fever or high temperature, cough and a nasal discharge, EHV can cause abortion and neurological disease (hind limb paralysis and incontinence). It is caught from other horses because they shed the virus in nasal secretions that form droplets in the air, for up to three weeks, and other horses can inhale the droplets. Some horses will be carriers of the virus and act as a reservoir for infection. They may not show signs of the disease until they become stressed, e.g. by transport, other illness or vaccination.

A diagnosis is usually made by taking a swab from the nose of the horse in order to attempt to isolate the virus. Another option is to take blood serum samples two weeks apart to look at rising antibody levels to the virus.

To prevent the disease there are vaccines available and these need to be given every two to three months to be effective.

The mare can be vaccinated when pregnant and this is normally done at 5, 7 and 9 months of gestation. Alternatively two vaccinations one month apart followed by 6 monthly boosters can be used. A foal can be vaccinated from three months old.

In cases of an outbreak of the neurological form of the disease, the National Trainers Federation and the Thoroughbred Breeders Association recommend a voluntary scheme of isolation policy on the premises, serology on all in-contact horses, separate positive and negative horses and re-test until all the horses have two negative samples.

Equine viral arteritis.

This is spread by nasal secretions, and venereally. The most significant infection can be that of stallions which may lead to them being chronic shedders of the virus. This can often necessitate castration to prevent infection of any mare that is covered.

It can cause severe respiratory signs and death in young foals, abortion swelling of the legs and underbelly, cough, and conjunctivitis. One of the most obvious clinical sign is “pink-eye” as a result of the conjunctivitis.

Diagnosis is by serology from a blood sample although previous vaccination will lead to the production of antibodies. There are vaccines to prevent the disease and understandably these are used most commonly in stallions top prevent permanent infection. It is important to confirm that the stallion has a negative blood test BEFORE vaccination is commenced to prevent confusion at a later date!!

Equine rhinovirus

This is associated with mild respiratory infections in horses caused by a picornavirus, and is similar to “a cold” in humans. However, it is very different to Equine Rhino-pneumonitis which is another name for Equine Herpes Virus infection.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Strangles

This is one of the most infectious diseases of horses and is caused by Streptococcus equi equi Strangles causes upper respiratory tract disease, hence the name, and is economically very significant. Also it involves a carrier status which can lead to periodic, possibly permanent, shedding of the bacteria.

Clinical signs are consistent with upper respiratory tract infections such as depression, fever or high temperature, cough and a thick, green nasal discharge. Abscessation of the lymph nodes or “glands”, especially under the jaw or around the throat can occur. These may burst externally or internally. Naso-pharyngeal swabs allow the bacteria to be grown or PCR testing to identify Strangles DNA.

Added complications may include spread of the infection to other lymph nodes around the body; this is known as “Bastard Strangles”. Also severe, extensive vasculitis may occur with very severe consequences.

Strep. equi zooepidemicus is a “sister” bacteria of strangles and can mimic some of the clinical signs although may be present as a normal resident of the respiratory tract. Occasionally it can cause more severe infections but this is rare.

Other less common bacterial infections include:-

Strep. pneumoniae

Pasteurella

Mycoplasma

The latter three more commonly cause lower respiratory tract disease in young horses causing signs of fever, nasal discharge, coughing and poor performance.

To diagnose bacterial infections, we have to take a sample of fluid from the airways by endoscopy. This is done by injecting a small amount of fluid into the windpipe and sucking it back up. This is to allow the bacteria to be grown in a laboratory to evaluate the best and most appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Other, more general, treatment for respiratory disease include rest, dust free environment, drugs such as “bute” to reduce temperature, and TLC.

Non infectious causes.

Equine Asthma/Recurrent Airway Obstruction/Small Airway Disease (aka COPD).

This is essentially an allergic disease, and can be associated with housing, hay, or pasture.

Signs are coughing, increased respiratory effort, watery nasal discharge, and exercise intolerance but with a normal temperature.

Diagnosis is usually made by history and clinical signs, but it can be confirmed by endoscopy and/or transtracheal wash to examine the types of cells present in the airways.

Treatment involves avoiding the allergens responsible, e.g. complete turnout if hay and stabling is responsible, soaking hay or feeding haylage, and using dust free shavings. Ventipulmin is a powder that goes into feed that can be used to open up the airways, and also steroids can be used to control severe cases. These are usually given orally. Sputulosin is sometimes used to water down any thick mucus in the airways, again this goes into the feed.

Allergy testing may allow exclusion of the specific allergy-causing substances or provide the information for desensitisation medication in the form of injections.

Human inhalers for asthma can be used to control RAO too, and although this works very well when used correctly, it does have to be administered several times a day and can be expensive.

Less common causes of chest problems

Aspiration pneumonia following inhalation of fluids or food

Heart disease

Lung abscesses

Lungworm

Tumours